China’s Lavish Pledge

Will $51 Billion Buy Africa’s Military Loyalty to Beijing?

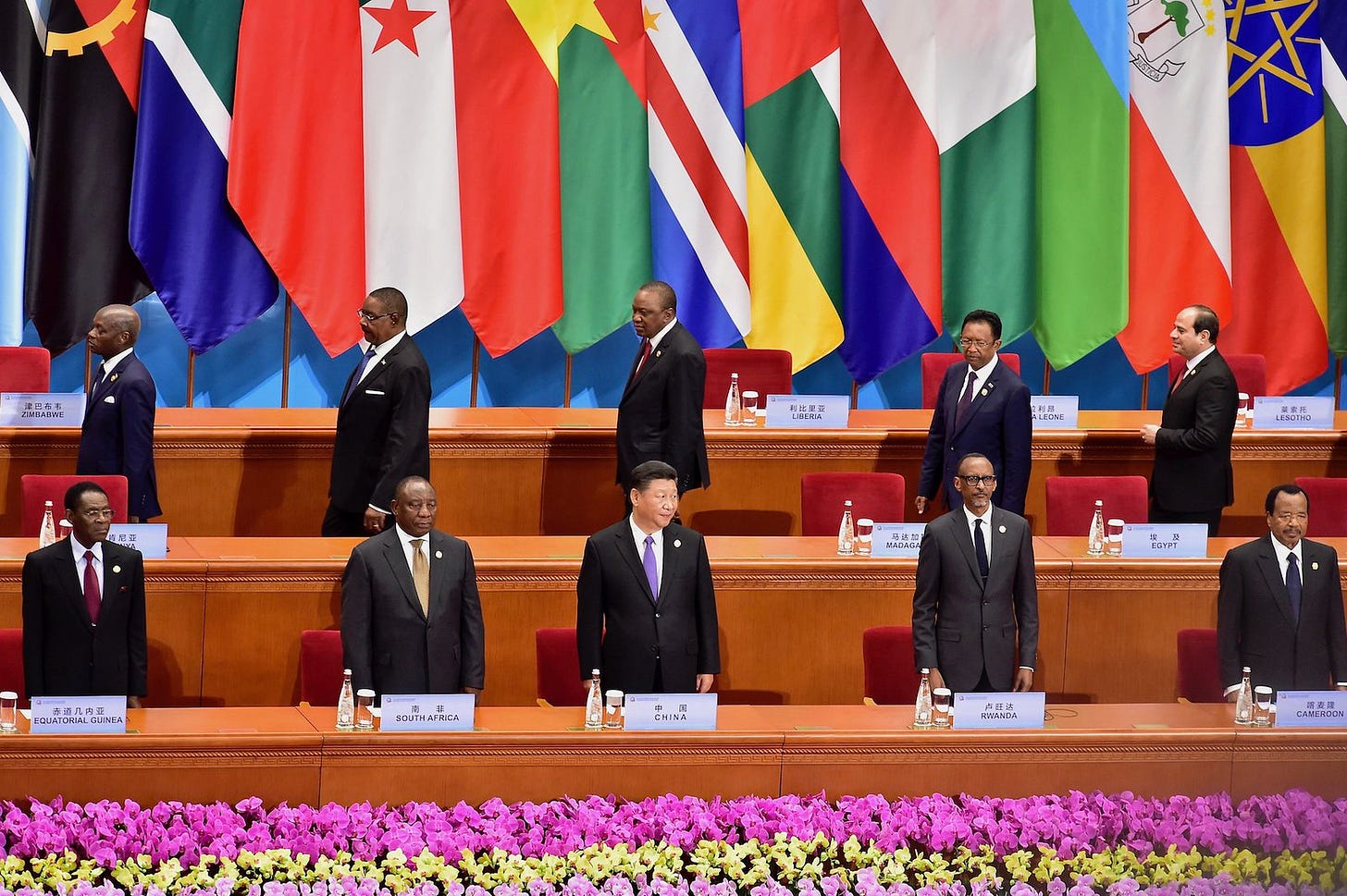

When President Xi Jinping announced a $51 billion aid package to Africa in September 2024, including $140 million for military training, the question seemed straightforward: would China’s aid-driven diplomacy finally eclipse American security influence on the continent? The focus on the United States is deliberate—despite the presence of other security actors like France, Russia, and Turkey in Africa. Washington remains the dominant external military partner through AFRICOM’s continent-wide infrastructure, training programs across 48 nations, and decades of institutional integration that no other power has replicated at scale. Yet framing the issue as a binary choice fundamentally misreads Africa’s strategic evolution. The real story is not about which superpower wins Africa’s loyalty, but how African states are engineering a multipolar security order that serves their interests precisely by refusing to choose.

The conventional analysis treats African military partnerships as commodities purchasable through aid packages. This transactional lens—more money equals more influence—reflects great power assumptions rather than African realities. China’s dramatic expansion from training 200 African officers annually in 2000 to 2,000 today, supplying equipment to 70% of African militaries, and conducting joint exercises like “Peace Unity-2024” with the Tanzanian army represents quantitative dominance. But military partnerships are not accounting ledgers. They function as complex ecosystems of trust, operational integration, institutional memory, and shared strategic culture developed over decades. China’s security engagement in Africa is indeed growing and evolving beyond its current state. Beijing actively invokes its Cold War-era support for African liberation movements—when the PLA provided training and equipment to independence fighters—to foster institutional memory and shared historical ties with contemporary African militaries.

China played an early role in supporting African liberation movements, providing military training to figures such as Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki and cultivating enduring networks with senior officers across the continent. Moreover, China is making long-term investments in cultivating future African military leadership by inviting young officers to train in Chinese institutions, mirroring the American strategy that created generations of U.S.-aligned commanders. However, at present, China’s $51 billion primarily addresses quantitative expansion, while its qualitative dimensions—the deep institutional integration, shared operational culture, and embedded advisory relationships that characterize mature security partnerships—remain underdeveloped compared to American engagement, though this gap may narrow as Chinese involvement matures.

Consider what African militaries actually need beyond equipment and infrastructure. Professional forces require institutional frameworks for civilian oversight, operational doctrines adaptable to diverse threats—from jihadist insurgencies to maritime piracy—intelligence architectures enabling rapid response, and command structures preventing the coups that have plagued the Sahel. China’s training currently emphasizes PLA doctrine and equipment operation—necessary but insufficient for building comprehensive military capacity. The character of Chinese military exercises reveals both limitations and evolution. Peace Unity focuses on protecting Belt and Road (BRI) infrastructure, reflecting a narrower security vision centered on Chinese asset protection.

Yet exercises like Eagles of Civilization and expanding naval drills suggest China’s military engagement is diversifying beyond BRI protection toward broader maritime security cooperation and peacekeeping capabilities. This evolution indicates Beijing recognizes that comprehensive security partnerships require more than infrastructure defense. Meanwhile, African debt to China, approaching $90 billion as of 2022, creates what economists call “crowding out”—debt service obligations that constrain defense budgets even as Chinese aid flows in, a paradox that undermines Beijing’s security investment.

The United States offers qualitatively different engagement through AFRICOM’s ecosystem of programs like Africa Endeavor, training 48 nations in cyber defense and NATO-interoperable command systems. More significantly, decades of partnership have created dense networks of personal relationships, shared operational experiences, and institutional linkages that transcend individual transactions. When Somali forces achieved gains against al-Shabaab through AFRICOM support, the victory demonstrated not just tactical training but years of embedded advising, intelligence fusion, and joint planning—capabilities that extend beyond funding alone and that China’s current three-year funding packages have yet to replicate. American military education programs have trained generations of African officers who now occupy senior command positions, creating institutional cultures aligned with professional military norms. China has also trained defense ministers and high-ranking officers across Africa, with some, like Zimbabwe’s senior leadership, maintaining decades-long ties to Chinese military institutions, suggesting that China’s institutional influence, while less documented, may be more substantial than typically acknowledged.

Yet acknowledging U.S. advantages does not mean assuming their permanence. American conditionality on governance and human rights—however principled—creates friction precisely when governments face security crises requiring rapid military responses. Washington’s competing priorities in Ukraine and the Indo-Pacific produce inconsistent African engagement that undermines partnership credibility. When African leaders compare China’s $51 billion commitment with America’s fragmented security assistance, the optics disadvantage Washington regardless of qualitative differences. Chinese flexibility and speed in delivering equipment contrast sharply with American procurement bureaucracy, making Beijing an attractive partner for governments needing immediate capability enhancements.

The complexity of African responses to this competition reveals the analytical error in treating the continent as a prize to be won. Kenya simultaneously hosts U.S. forces at Manda Bay and purchases Chinese armored vehicles—not from confusion but from strategic calculation. Ethiopia accepts Chinese BRI loans while depending on U.S. military counterinsurgency support. South Africa engages BRICS militarily but participates in AFRICOM’s African Chiefs of Defense Conferences. This is not hedging as a temporary expedient but hedging as a permanent strategy, reflecting hard lessons from Cold War proxy conflicts when exclusive alignments made African states pawns rather than players.

The multipolar security architecture emerging across Africa represents a fundamental shift in international relations. Rather than great powers shaping African security environments, African states are exploiting great power competition to expand their strategic autonomy. By maintaining diverse partnerships, they gain negotiating leverage with all parties, access to complementary capabilities unavailable from single sources, and insurance against any partner withdrawing support. So, China’s $51 billion enhances this system by introducing competition that improves terms from all partners, but cannot overturn it because exclusivity contradicts the strategic logic African states have carefully constructed.

This framework explains why the question “will China buy African states’ military loyalty?” misunderstands the dynamics at play. Loyalty implies subordination; African states seek military partnership. Beijing’s funding does contribute to enhancing operational capabilities—Chinese equipment, training, and infrastructure improve African militaries’ technical capacity. However, this operational enhancement translates into access and goodwill, not strategic alignment or exclusive loyalty. The Peace Unity exercises showcase Chinese capabilities but do not displace Flintlock or Justified Accord—they complement them within portfolios of diverse security relationships. As long as African states prioritize strategic autonomy over great power patronage, neither Chinese financial inducements nor American operational advantages will prove decisive.

The future of African security partnerships depends less on what Beijing or Washington offers than on how effectively African institutions translate external engagement into continental capacity. The African Union’s emphasis on “African solutions to African problems” reflects growing confidence, yet resource constraints ensure external partnerships remain relevant. Interestingly, China has appropriated this principle in its security engagement with the continent, portraying its assistance as enhancing rather than supplanting African agency—a rhetorical positioning that resonates with continental aspirations, even as it raises questions about whether Beijing’s involvement truly empowers African institutions or creates new forms of dependence. In other words, whether these partnerships build African independence or create new dependencies. China’s $51 billion poses this question urgently—will it finance infrastructure enabling African force projection, or infrastructure requiring Chinese protection? The answer will determine not whether China buys African loyalty, but whether Africa maintains the strategic autonomy it is fighting to achieve.